When the UN undertook its first global assessment of soils in 2015, it found that a third of the planet’s soil is either moderately or highly degraded, reducing its ability to grow crops. The continuing degradation of the soil could “severely damage food production and food security, amplify food-price volatility, and potentially plunge millions of people into hunger and poverty.”

Causes of soil degradation include heavy plowing and tilling, the application of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, soil compaction by heavy machinery, monocropping and the resulting erosion from all of the above. In other words, intensive agriculture threatens our ability to grow food.

Regenerative agriculture, on the other hand, heals the soil, working with nature rather than fighting with or attempting to control it (as Nature laughs). Regeneration goes beyond the aim of sustainability, to “do not harm,” and instead, contributes more to the soil than it extracts from it.

Based on the traditional knowledge of Indigenous peoples around the world, regenerative farming practices include:

Eliminating or reducing plowing and tillage

Eliminating synthetic pesticides and fertilizers

Planting diverse crops, including cover crops—and rotating them

Managing and incorporating grazing animals

Applying compost

These practices draw down carbon from the atmosphere and recarbonate the soil. They improve soil health, increase the resiliency and productivity of farms and their communities and increase the nutrition in food.

Given that a mere 1.4 percent of the US population works as farmers, most of you reading this newsletter do not work the land, where you could implement these strategies directly. We individuals can still play a role, however.

Support local small farmers

Generally, smaller farmers are more likely to follow at least some of these regenerative practices. Some farmers’ markets help ensure it. Chicago’s Green City Market was the first farmers’ market in the US to require all of its vendors to undergo certification by at least one of several third parties, including USDA Certified Organic, Food Alliance Certified and Animal Welfare Approved. If you don’t know how your local farmers grow their food and want to know, ask.

Either buy directly from smaller producers at a farmers’ market or sign up for their CSA (community-supported agriculture, a subscription produce box). Buying direct helps farmers stay in business. For every dollar we spend at the grocery store, the farmers who feed us receive on average only 15 cents, according to a recent joint investigation by The Guardian and Food & Water Watch. The rest of our dollar pays for marketing and processing (the products in grocery stores undergo heavy doses of both!). When we shop at the farmers’ market, on the other hand, about 90 cents of our dollar goes directly to the farmer, according to the advocacy group, Farmers Market Coalition. (See Day 20 for more on the importance of shopping small and local.)

In addition to higher revenues, smaller farmers also enjoy more autonomy when they sell directly to the public. In a typical large American grocery store, Big Food largely controls what sits on store shelves. Consider some numbers from that joint Guardian–Food & Water Watch investigation:

4 companies supply 79% of key grocery items found in a typical American grocery store

3 companies sell 93% of all soda

3 control 73% of the cereal market

4 control 80% of beef processing and 70% of pork processing

Like a retail monoculture, the aisles of a giant American supermarket, while seemingly bursting with choice, offer very little. With this kind of concentrated power, the influential and wealthy mega-companies call the shots.

The economic power of these corporations enables them to wield huge political influence, so we have a system in which farmers are on a treadmill just trying to stay afloat. Basically there’s a handful of individuals in the world, mostly white men, who make money by dictating who farms, what gets farmed and who gets to eat. Consumer choice is an illusion; the transnationals control everything in this extractive agricultural model. — Joe Maxwell, president of Family Farm Action.

Become a farmer

If you recently graduated from college or you’ve dreamed of starting your own small farm or homestead, joining WWOOF (Worldwide Opportunities on Organic Farms) might be for you. The WWOOF network connects volunteers wanting to learn about organic food and self-sufficient lifestyles with small organic farms (or allotments, vineyards, gardens, woodlands and so on) around the world. In exchange for their work, volunteers receive food and accommodation—and they learn life-long skills. Some WWOOFers move around to several farms to learn all they can before they start their own small farms.

Now, an organic farm is not necessarily a regenerative one. But keep in mind that WWOOF began in the UK in 1971, when the term “organic” held more meaning. Big Food has since co-opted the term and grows organic food on an industrial scale, in monocultures that present many of the same problems as non-organic monocultures, but without synthetic fertilizers and pesticides.

If you are considering a future in farming, check out the anthology, Letters to a Young Farmer.

Plant a garden

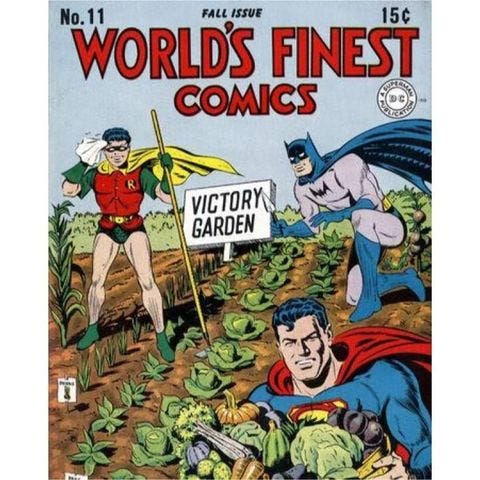

When the pandemic exposed the cracks in our food supply, people started planting “Corona Victory Gardens,” similar to the backyard, school and community gardens that, during World War II, provided about 40 percent of America’s fresh produce during another time of uncertainty.

Perhaps you’d prefer to plant a pollinator garden (or both!). The use of pesticides and clearing of habitat on industrial farms have put pollinator populations at risk. Find resources for helping pollinators through the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, an international, science-based nonprofit, dedicated to conserving invertebrates and their habitats. If you do plant and nurture a pollinator habitat, you can add it to the Xerces map here.

Planting a pollinator garden may sound like a pretty deficient counter to agribusiness but it could make all the difference to pollinators in your area. Even small urban gardens help conserve bees. Last year in Palo Alto and Mountain View (my backyard, but not literally), urban gardens and residential areas enabled the beleaguered monarch butterfly to flourish.

What we are learning is that the urban gardens and residential areas could be very critical. When we think of endangered species, they’re usually out in the wild. But there’s habitat in everyone’s backyards. — Robert Coffan, chair of the nonprofit Western Monarch Advocates

While replenishing the soil in your yard or community garden, you’ll also help replenish your gut bacteria—another victim of the Western (now global) diet of ultra-processed foods and modern lifestyles—by coming into contact with the microbes in soil.

The soil microbiome likely evolved in tandem with the human microbiome and its estimated 39 trillion microbes that occupy our noses and mouths, our armpits and the palms of our hands, and most of all, our guts—particularly our large intestines. Our health is not only predicated on the activity of the microbes in our guts, but on the microbes we ingest both directly (from purposeful geophagy, or accidental dirt ingestion) and indirectly (in the form of plant crops) from the soil. FoodPrint, “The Connection Between Soil Microbiomes and Gut Microbiomes”

Everything is interconnected, something industrial agriculture disregarded.

Only four newsletters left to go! I hope you’ve found these daily newsletters useful. Thank you for reading!

There is a wonderful Netflix movie called “The Biggest Little Farm” that depicts a regenerative, organic farm. Gave me a much deeper appreciation and understanding of the issues farmers face in growing our food. I grow both a pollinator and vegetable garden and encouraging the pollinators paid off this past summer with bumper crops of beans, tomatoes and carrots (despite the bunny that tried to burrow in the carrot patch!).

In California, there are two kinds of farmers markets. Look for the Ones that are certified. This means that all the produce is grown locally and if the farmer says it is Organic, it is.

Ron Finely, A.K.A. The Gangsta Gardener, has a popular TED talk. It explores his experience in bringing home grown food to an area that has more drive throughs than drive bys.